Adam Linz is a double bassist and an eminent force on Twin Cities jazz and creative music scenes. Linz has been a part of some of the area’s most exciting bands over the last 20 years, most notably as co-leader of Fat Kid Wednesdays. In this two-part interview, the bassist, composer, band leader and teacher offers reflections on his musical journey, field notes from life as a musician, and insights into the changing dynamics of the Twin Cities music scene.

What made you pick up the bass?

I picked up electric bass first when I was 12 or 13. We had just moved to Minnesota and I was coming from Mississippi, so I had a southern drawl. It was kind of hard to make friends up here. Minnesota kids can be a little off-putting and bullyish at first. But I had cousins up here and they introduced me to metal and alternative music.

I was also an MTV kid, you know what I mean? That’s kind of the difference between my generation and your generation [Linz is referring to musicians born in the 90s]. We learned about music through MTV, and the great thing about MTV was that it wasn’t genre-based. Anybody who could afford to make a video and get it up there, could get it up there, and it would be in a rotation. In the early days they didn’t have that many videos, so I was seeing Tom Petty videos, but I’m also seeing Duran Duran videos. I’m also seeing Run-DMC videos, and I’m also seeing bands like Europe, Bon Jovi and Cinderella. I was into hard rock: Van Halen, RATT, Iron Maiden, Slayer, Metallica. I didn’t want to play guitar because I had little hands, my mom’s hands. I always felt my fingers were a little chubby. I always thought guitar players had long, nimbly hands. I’m also left-handed.

My uncle, Tom Hubbard, was an upright bass player from New York. He was a long-time veteran player of the Twin Cities. We went up to Music Connection in Forest Lake. They didn’t have any left-handed basses. But they had a nice little beginner Squire P-bass that was cream white with a cream pickguard, and a little amp. So I bought it, and it was right-handed, but I adjusted. I played electric for a number of years, and then played fretless, and then got a stick upright eventually.

Once you started on the double bass, when did you realize you could hang with anybody, or that you weren’t afraid to play with anybody?

Oh man, well I still self-doubt that question. But, I know what you’re talking about. Even after I studied out east, and hung in New York City, I was always putting myself beneath people as a player. I’m not very cocky, although some people might argue that. I’m an only child and we moved around a lot. I was pretty shy because I was used to being the new kid. Even when I went to William Paterson, I had culture shock. A kind of East Coast hardness that goes on out there, I wasn’t really used to that.

I remember one day during the Clown Lounge era – which is the club we played with Fat Kid Wednesdays for almost 11 years. It happened during the first couple years of playing there with those guys on a weekly basis. I just remember waking up one day and I was forever changed. It wasn’t like a religious experience, but when I played the Monday night before I was unstoppable in my mind. I imagine athletes go through this, too. You have these moments when you are literally changed by what you’re doing because it’s so creative and it’s so in the moment. It’s hard to explain to people sometimes, right? So, I remember waking up and being like “Dude, I’m in this now. There’s really no turning back. Everything I’ve ever wanted out of this is coming true. And holy shit, look at the amount of work we’re gonna have to do now to keep this up.”

I remember waking up and being super happy. I felt like I had, maybe, gotten beyond a huge plateau that I was sitting on. When you do a bunch of things for a long time, and then you finally digest them, they have more meaning. Viewpoints are changed. There are things you don’t like as a kid, then you grow up and say, “I love that.” Whether it’s a certain type of music, or a player, or, you know, Richard Davis (laughs). Your tastes change as you become older. I’m not gonna say you become wiser, but, you have more experience in the world.

I was teaching a bunch at that time, too, and just going full bore, playing around the Twin Cities five, six nights a week, multiple gigs a day. I was playing a lot with Benny Weinbeck, subbing for Gordy Johnson. I was doing a lot of vocal gigs, and then playing with Fat Kids. At that time, I was involved in a lot of scenes. I didn’t say no to a lot of things back then, like most young people do now.

It took a while. It wasn’t like I was 18 and was like, “Man, I can hang with anybody.” But then, after a while, you keep collecting records and you start to hear certain records with musicians who you thought were invincible, and you say, “Hey, look they didn’t have the greatest day, here.” Or you find things in your own life and say, “Man, today I just sucked on that gig.” With Fat Kids, there were nights when one of us showed up and was like, “Dudes I got nothin, I got nothing in the tank.” And then by the end of the gig you’re like, “Man I got it, I got it back, you know, my friends helped me. They propped me up, and supported me, and the audience was great, and there was a little money at the end of the night, and it’s 2 a.m., and I feel better.”

And now at this age, you get old enough where you don’t give a shit anymore. You know when you’re young and you’re like, “What if blah-blah-blah called me, could I do that?” But what you realize is that “blah-blah-blah” who’s calling you, he wants you, or she wants you, or whoever. They want you, they want your voice.

What ends up happening eventually, and I think a lot of Twin Cities musicians go through this, the more that you become an artist, the fewer and fewer people want to play with you because you’re risky to play with. You might play a standard with them but you might start changing the chords on them. That’s a no-no here in Minnesota. Then you start to change a little bit.

Fast-forward to now, you are considered a bass virtuoso by many people in the Twin Cities…

Jeez, I hope not. That would be horrible.

What do you mean?

Well, I mean come on. We’re students of this stuff for life and… a virtuoso? A virtuoso is somebody with natural ability. I never had that stuff, Sam. I’ve talked about this before, having to fight for every scrap of what you can do on the bass and surviving it. But thank you, it’s a great compliment.

I think of Anthony Cox as a virtuoso, for sure, somebody who can do a lot more things on the instrument than I can do. But we can still sit down and talk about it, and laugh about it. “What are you doing this week,” we ask each other, “that is crushing your soul on the bass?” (laughs).

Well, I think you’re viewed as someone who has figured out how to play the instrument in ways that very few people have been able to. That begs the question: Is playing this music more about talent or hard work, or is it some combination of the two?

Bill Evans used to talk about that. He would talk about how he’d rather play with somebody with no natural ability who had to work for it because the people with natural ability take it for granted after a while, unfortunately.

I’ve seen these superbands, you know what I mean, where they put five leaders together and it never quite works. Money wise, it works, because the festivals are like, “We got blah-blah-blah on the bass, we got blah-blah-blah on the piano, and here’s blah-blah-blah on the sax.”

But you look at somebody like Brian Blade’s fellowship band, or… I’m trying to think of groups where it’s not made up of world famous leaders… those are my favorite groups, where I’m like, “I don’t know who this person is from Detroit, or Washington, or San Fransisco, but I like what they’re doing.”

Where does the confidence come from?

Eventually you play with enough people from other places who are very well recognized, and you go, “Yeah, I can do this, I can hang. I can do this without freaking out. I can do this without having the dude hate me. I can do this and still bring my personality out through it. I can do this without selling out my values as a musician.”

There probably needs to be a lot more of that in our industry for sure. It’s a very fine line that you walk being a creative musician, being a jobbing musician, being a teacher. You’re really making yourself vulnerable for people to nitpick you and have opinions about you and your playing. But they’ll never be able to have the memories that you have. For me, it was playing with Evan Parker, or playing with François Tusques and Noel McGhie in a little town in Western France, or going down to South America and playing with a bunch of friends who live in Chile and Argentina.

My most memorable times playing are with people who were never famous. Most famous people I find to be pretty trite, pretty boring people, pretty crude. I’ve gotten hired by very famous people to play creative music, and you soon realize that you’re there to fill a role and it’s not about you. It’s about this person and they’re here to sell and promote themselves. You’re there as a prop. And once the person moves on, you’re back home taking out the garbage. And that’s how our life is: we go through these extreme ups with a lot of down valley. And I think what happens in that down time is what really determines what comes out on stage.

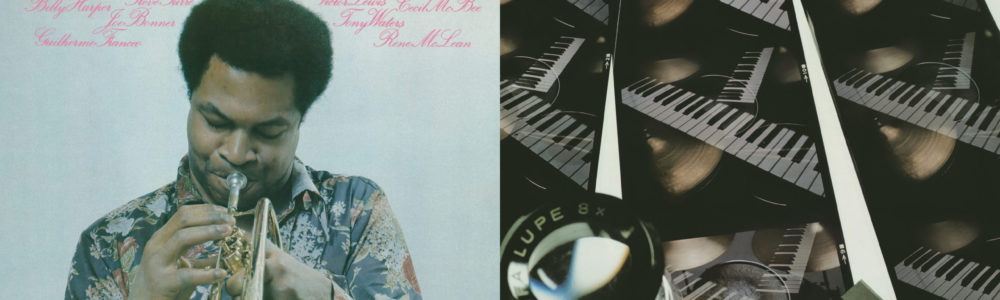

You’re also known as an audiophile and connoisseur of vinyl. How does being a collector, student and listener of the music relate to being a performer?

A lot of musicians never know the side of how their stuff gets distributed around the world, or how records are made, or who works in that record store. You and I are lucky that we live in a town where, per capita, we have more record stores than any other US city. Maybe because the Mississippi River is here, maybe because a lot of American business was invented in Minnesota. Whether we’re talking Cargill or 3M or the Donaldson’s or the Target Corporation or Honeywell.

So, I wouldn’t call myself an audiophile either. I own things that I love, obviously. I think of an audiophile as someone who might be a completist collector. I know dudes that shop at the record store [Linz is referring to Barely Brothers Records in Saint Paul, where he works] and they bring a booklet and say, “Here’s the Prestige records I’m missing.” (laughs) “Here’s the Blue Note records I’m missing.” To them it’s a different thing.

But I’ve worked in record stores, worked in distribution, and worked in recording studios. Those times are very memorable to me. Those are communities of people behind the scenes of famous musicians. We’ve had a lot of very successful jazz clubs in the Twin Cities that have been able to bring a lot of big artists here. But without people going out and buying the records, it wouldn’t be what it is. It’s a very, very important part of the process.

Anybody who’s young, I tell them: “Go get a job at a record store. Go get a job at a warehouse. Go work in a kitchen. Go bale hay for the summer. Go do something where you think, “Oh man, music now is even more important to me. That shit I did today, that’s hard. That’s real labor, that’s real work.”

I think us, as musicians, we get a little arrogant, like, “Oh I put in all this work when I was a kid. I lost my youth. I lost my college years because I was in a concrete room practicing.” Right? Usually with a bunch of Y-chromosome dudes. I mean dude, who goes to college being like “Yeah, I’m in a sweaty box with a bunch of dudes who are all egomaniacs, right, because they’re all trying to get better.”

It’s almost like being an Olympic athlete. It’s competitive, you know? And you work hard so you can party hard, but you’re not like a normal college student. You’re not a normal person. After music takes a hold of you and you decide to go down this path holding its hand, you are forever changed. At some point, you can stop, but usually when you back out of it and try to do something else full time, you probably won’t come back to it. It’s just like being an athlete. Once you stop swimming six hours a day, or lifting weights four hours a day, things change and when you try to go back it’s really, really difficult.

I’ve had lots of people over my lifetime tell me to quit when things get difficult. “Just stop,” they say. “Go get a normal job, have a family.” But that was never my goal when I was 14, going to New York in the summer, hanging with my uncle, going to all these jazz clubs, being like, “I want that.”

But once you make that decision, you’re in it full on, and it becomes a lifelong endurance test in a way. How much can you take? Because there’s gonna be ups and downs to this. For all the good times you have, you’re gonna have probably 10 times as many bad times. But you gotta know how to weather it and keep moving forward slowly. A lotta guys burn out, too. The music after a while doesn’t fulfill them, so drugs, alcohol, sex, money, fame – all that stuff starts to creep in. You’re constantly checking yourself because you are your only boss.

Do you think it’s possible to innovate in today’s jazz world, or do you think all the innovation has happened and now it’s just about preserving tradition?

The music continues to change for better or for worse. I think innovation is really important. I also think we live in a time now that’s a little different than when I was coming up in the 90s. People aren’t looking for new things now; they want things to be very comfortable. We live in a society now, in America, where you shouldn’t think outside the box, where you should go along with the norm. That really hurts our scene of people here – Paul Metzger and I call it the freakshow scene – those people need an outlet too.

One of the greatest things I ever saw was a guy that used to play this place called Gus Lucky’s. I saw a guy put on a miner’s cap and a wife beater that was super dirty. He had a piece of sheet metal with a bunch of contact mics on it. At different variables, he would just scrape different shovels across it with various effects on it. It was brilliant! It was unbelievable. (laughs)

So, we have to have room for the shovel guy. We have to have room for the guy that plays weather balloons. We have to have room for the guy that brings his laptop to the gig. And that scares jazz, for sure. But we’ve had people over the years, like the trombonist George Lewis, say, “You shouldn’t be afraid of this technology.” Even jazz instruments have changed over time. Saxophones were not always Selmer Mark VI’s. Basses didn’t always have four strings. Drums have come along hugely.

If you become a jazz musician you’re part of a lifelong tradition of learning an instrument. I think that’s lost today. So many kids are told, “Well, you can learn this, but you’re not gonna do this for your living because there’s no way you can.” They’re taught to give up before they even dream. And that’s hard.

What do you say if you encounter a kid who believes that?

That’s why I still like to teach. I tell kids, “You can do it, and if after a while it’s not happening, you might want to think whether or not it’s for you.” I don’t want to be the guy that says everybody can do this, because that’s not true. Not everybody has the temperament to do this. I’m not trying to crush anybody’s dream. I’m just trying to tell them that as they go through this, they have to look at themselves and constantly ask: “What are we doing? Why am I doing this? Am I doing this for money? Am I doing this for creative outlet? Am I doing this because I love it? Am I doing this because I hate it? Am I doing this because I’m trapped in it? Is it positive? Is it negative? Is it right down the middle?”

There’s so many questions that go into it. That’s what’s great about it. It’s great when you play with somebody new on stage and you can tell they’ve done the same amount of work as you. You took two totally different paths, but you come together at the same spot, at the same moment, and probably played some great music together.

Right on.

And then it gets super deep, and you’re like, “Oh my god, Sun Ra is a lifetime of study no matter what path you choose through it.”

During your time at MacPhail you taught many musicians who are now contributing to the Twin Cities scene, people like Patrick Adkins, Levi Schwartzberg, DeCarlo Jackson, Ben Ehrlich, Jordan Anderson, Peter Goggin, Charlie Lincoln, Ivan Cunningham, Sophia Kickhofel – and there’s a bunch of names I haven’t listed. Can you talk about your time with those students and what your expectations are for this generation?

I was lucky because the Dakota Combo offered me the experience to work with kids I handpicked. We were looking to put together the best youth jazz band that we could, at the time. I definitely auditioned players that were better than the players who ended up in the Dakota Combo, but maybe they were cocky in their audition, maybe they were one of those people in creative music where you’re like, “I don’t want to have a five-minute conversation with this guy.”

But I was so lucky to work with you guys. It was nice because when I started doing Dakota Combo, the MITY program [Minnesota Institute for Talented Youth] was still happening in the summer at Macalester. I was able to have contact – between the Dakota Combo and teaching at MacPhail in the summer and doing MITY and some other jazz camps – I bet I’ve had access to teaching thousands and thousands of kids at varying levels.

Teaching you guys when you were young and being able to put you on a path, just kind of nudge you, that was my whole thing. I hope that came across and I was never like, “Here’s the way to do it.” I was like, “Here’s 10 ways to do it. Now find the one that works for you. And the amount of work you put into this will come out of it.” Some of you guys were supernaturally talented. Some of you guys were incredibly hardworking. And a lot of you guys were a combination of those things.

Being able to get into the vocabulary of jazz, get into some tunes, get into some composers, not just make it the Marsalis family style of teaching that says, “Oh you’re a kid, you don’t get to play anything after 1955″… Bullshit! And also making sure that you guys composed, trying to get you guys to write this music which is incredibly difficult as you know.

But man, having access to all of you was great. We tried to make the most of that time in that rehearsal room up there and at our gigs, and I think it really came across in the scene. I think for a number of years, a lot of amazing music came out of that ensemble. Some of you guys got to make CDs.

I used to joke to you guys – do you remember this? – I’m just teaching you guys so that one day you’ll hire me (laughs). But that is kind of my goal, and I remember that about New York. Guys would be your teacher and then all of a sudden, they’re hiring you for their band, or you’re hiring them for these little gigs that you’re getting, and they’re incredibly grateful because they’re playing outside of the circle of friends that they always play with. And, as you know, this music can end friendships over time. Opinions and attitudes change.

It’s nice to see you all go out into the world, and then have a lot of you come back. That doesn’t happen in a lot of cities. A lot of guys go out in the world and they don’t want to come back. We’re very lucky here. I can’t say that enough. But we still have to be vigilant. We still have to remind people about what we do. We have to stay vigilant because we’ve lost a lot of venues. And there’s more and more people who wanna play this music every day, who want to be professional, and it’s getting a little swampy out there.

My goal is that you guys, hopefully, remember what we always talked about: staying positive, having a family of musicians that you can talk to and lean on, make your career. You guys all went different places. Hopefully the people you’ve met from those places want to come play here, and you guys can make that happen. It’s not just about being a musician. It’s about booking shows and doing promotion and trying to figure out the money, trying to make sure that you don’t lose your ass on it. You gotta make those things happen, because if you don’t do it, nobody’s gonna do it for you.

All of you guys have been so fantastic in your philosophies, in your kindness. Nothing pisses me off more than somebody who has talent and is a great musician and is a total asshole. Those people I have no time for anymore. I just can’t put up because I’ve known and seen so many. Hopefully, my goal with teaching was to give you a foundation to build on, so that you can go out and live your own dreams and have your own experiences. And hopefully all of you guys teach a little bit.

Those years at MacPhail, just having access to the best young players in town… I loved going to rehearsals (laughs). I loved it man. And we would do it at night, so it was great. I love when jazz happens in the dark.