Adam Linz is a double bassist and an eminent force on Twin Cities jazz and creative music scenes. Linz has been a part of some of the area’s most exciting bands over the last 20 years, most notably as co-leader of Fat Kid Wednesdays. In this two-part interview, the bassist, composer, band leader and teacher offers reflections on his musical journey, field notes from life as a musician, and insights into the changing dynamics of the Twin Cities music scene. (see Part 1)

You’ve played all around the world with some great musicians, but is there a gig that you’ve played that’s more memorable than the rest?

Sure, it was the first time Fat Kid Wednesdays went to Europe and we played at Sons D’Hiver. It was just a one-off gig. We hadn’t even recorded the record yet I don’t believe [The Art of Cherry]. Mike had been to Europe. J.T had been to Spain with Jim Anton, but that was the first leg of us going over there many times as a trio. I think I’m 25 or 26 years old at the time. This is the biggest festival I’ve played in my life so far. We learned how the music system works over there. We had no idea that there was a Ministry of Culture, or that the people running the festival were government employees, and that a lot of the money comes from the government there. We had nice vans, nice drivers, a nice hotel, and all these people were taking care of us.

We saw Anthony Cox there by surprise. I was in the hotel lobby, and Anthony Cox walked in. He looked like Laurence Fishburne out of the Matrix: bald head, matrix glasses on without the rims, and a big trench coat. He was styling. I didn’t know he was gonna be there so it was incredible. I had known Anthony for 10 years at that point. Having him there was special. He would hang out with us. He’d go out at night with us and see the city. We walked in a really nice part of the Bastille where the French Revolution took place, right next to the French opera house. So we’re in a beautiful, highly political area. The Moulin Rouge is right around the corner, and there’s a great record store called Bimbo Tower.

We met so many people that trip who would become lifelong friends, many journalists and photographers. We met Guy le Querrec. We rolled up on the gig for soundcheck and all of sudden I see Mike Lewis freaking out. Remember, Mike Lewis does not get that excited about people. He’s pretty calm even around famous people. But, Mike started freaking out and he was like, “Yo, there’s Guy,” and I was like, “Who’s Guy?”

I didn’t realize it was Guy le Querrec, one of the most famous photographers in the world, who runs a photo journal magazine called Magnum. Guy le Querrec shot Coltrane, Miles and Mingus, the whole sixties thing that went down in France. He’s good friends with Archie Shepp. And so there’s Guy and he just starts snapping away, shooting hundreds of photos of us on black and white film. It was like something out of a dream. And I’m getting paid to be there.

How did it feel on the bandstand?

Ah man, we played this really cool old church that had been turned into a dance studio. And, it felt great. It was winter so the festival people had built tunnels and tents in the parking lot. There were heaters in there and journalists and chefs making food. It was crazy. You’ve never seen anything like this in the States, unless you’re playing a winery or the California Monterey Jazz Festival. And all the musicians that we’re meeting were like, “Yeah, yeah whatever, this is what I’m used to.”

But to do that with those guys at that time, that was one of the most memorable experiences of my life. I think about it often. I highly cherish that I was able to go to Europe for the first time with a great band with two guys who were my best friends. It was special to have Anthony there, Jean Rochard there, and all these people who were excited about what we were doing. At that time back in the States, the Clown Lounge was just getting going. We couldn’t give our shit away here, you know. People were like, “Yeah you guys are the newbies here in the Twin Cities.”

To go over there and be treated like that at that age was something that I do not take for granted. I feel very grateful anytime anybody’s willing to take care of us. I know the amount of work that goes into pulling that stuff off. And I’m really grateful for the people that brought us and took a chance on us, and opened the doors to the rest of Europe.

That’s beautiful, man. Here’s a similar question but slightly inverted, as an audience member is there a gig you’ve attended that’s unique for some reason, that you’ll always remember?

Does it have to be jazz?

No

You gotta remember, I came to jazz through the backdoor of rock and hip-hop. I graduated high school in 1993. I caught the brunt of the music industry at its best. You know what I mean? Between First Avenue, between the Met Center (where the Mall of America is now), I saw some amazing shows whether it was Iron Maiden, Metallica, Public Enemy, Björk, Fela Kuti.

One gig comes to mind which happened at the Berlin Jazz Festival. There was a band for a feature that they had been working on for a long time. It was a band made up of very very old gentlemen, about 50 musicians. Everybody that was original to the group was 85 years old and older. It was a bunch of Jewish and Palestinian dudes who had played back in the day before the conflict got really out of hand. And they kept playing across the borders as the years would go on. This was a big reunion gig. So you got like ten zithers, you got your typical instruments from those areas, you got drums, along with bass, and three or four vocalists. It was beautiful, man, and it probably never happened again.

I saw Peter Kowald solo in Chicago once. That was amazing. When I first got to New York and I was in school, I remember going to see Lovano at the Blue Note the first night I was there. I remember being on the guest list, and having Billy Hart come up and say, “Hey, guys what’s going on? Are you guys at William Paterson? Awesome, I hope I get to play with you one day.”

And you’re just like, “Uhh, what happened?” And all of a sudden you’re part of the tribe. You’re kind of the initiate, but you’re a face to those guys. And every time I would see Billy Hart, he would be like, “Twin Cities, how you doing?” (laughs). He always remembered.

That’s the thing about this stuff: It happens, and I think your generation is gonna get to see it, and the next generation is gonna get to see it, but it doesn’t always work out that way. You gotta hold on to that stuff and really remember and not be super screwed up when you go to those shows.

I’ve always seen you as a jazz musician who studies the entire history of the music. So, what does the phrase “from ragtime to no time” mean to you?

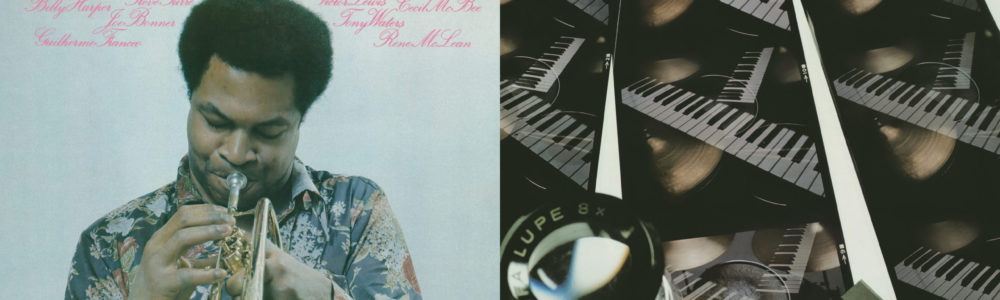

Well, that’s a record, you know? It’s a Beaver Harris Ensemble record where they took a bunch of older guys from the rag period in New Orleans – Doc Cheatham and those guys – and put ‘em with a bunch of free jazz guys and made a great record.

Do you remember that story where Mingus – who is considered the extension of Ellington – is showing Ellington a new tune on the piano, and Charlie’s like, “Check this chord. This is crazy. I just learned this and just learned this.” And Ellington says, “Why are we going backwards 30 years in my life?”

You gotta remember that flappers, ragtime, depression era music, pre-be bop, pre-Swing music… that stuff was out, man. It was the hip-hop of its time, or, the modern music of its time. We take it for granted right, because ever since junior high we’ve had jazz band. You gotta remember, that was like going to the hip-hop club. Sorry, there are no more hip-hop clubs today. Back in the day, that was street music, that was trap.

Ragtime to no time? Definitely part of the jazz idiom, part of a philosophy that maybe I got from somebody like Phil Hey, or musicians like Dave Karr and Steve Kenny. That’s the great thing about the Twin Cities, there’s always been a heavy influence on everything. Whether you’re gonna play with the Wolverine Jazz band, or you’re gonna play a solo free improv gig at Khyber Pass, or you’re gonna play with your trio at Jazz Central. You are expected to at least be checking out the canon. And I think a lot of the younger guys maybe have gotten away from that a little bit because they pick one thing and think there’s financial outcome in that one thing.

I was lucky enough to grow up in a time period where there was a lot of combining music, a lot of alternative music. Pick a band like Faith No More. Is it hip-hop, is it metal, is it avant-garde, is it rock? They’re doing the Nestle chocolate commerical song at their gig because they thought it was beautiful, you know?

I can go see Lincoln Center one night and appreciate what’s going on on stage, the quality of what’s being presented. And then the next night I can see Globe Unity Orchestra and still be just as charged up. I’m lucky. I never had anybody say, “You gotta put handcuffs on this. you can’t check this out or this out.” Because I grew up in an era of cassettes turning into CDs and then CDs turning back into vinyl, and growing up when you could go to the record store and say, “What is this? Who’s John Lindblom? Who’s Bill Dixon? Who’s Elliott Carter?”

It comes from hip-hop too because hip-hop is a sampling style of music. All of a sudden, oh, they’re using this classical sample combined with this organ riff from Jimmy Smith combined with a breakbeat from James Brown combined with a bass line from Sam Rivers’ Contours with Ron Carter, and you’re like, “That’s cool as shit,” you know? And then you come up with something else.

I just think that gamut, that’s a very Twin Cities thing. I don’t know if it’s because we’re cut off from the world for so much of the year when it’s cold here. And we’ve always had the avant-garde here, from the Walker to a lot of the dance companies. You’re very lucky to live in a town where you can go see Modern art anytime you want.

Talk about your newest band, Le Percheron, how that came about, and what you’re trying to do with that group?

After Fat Kid Wednesdays had a 10-year run, we slowed down. The guys, including myself, were all doing so many projects. Michael especially was touring a lot, whether it was with Andrew Bird or Bon Iver. I felt like it was time to do me. Fat Kids is great, but you gotta remember Fat Kids is a leaderless trio and, while that sounds fantastic, there’s a lot of problems that can come from that. I might bring something to the group but it might get pushed out because somebody thinks it’s not right for the band. Again, the leaderless trio is very difficult to ascertain. If you don’t have a leader saying, “We’re gonna do this, and it’s gonna go look like this,” that can be hard. Sometimes it’s easier to have a leader than have uncertainty about what the band’s gonna do or who’s in control.

I’m always late to the game, people were like, “Why didn’t you do this 10 years ago?” And I was like, “Man, I just want to have my own group now.” I love being able to have vibes, cornet, bass, drums. I’m a huge Don Cherry fan. One of my favorite Don Cherry groups is that European quartet with Karl Berger. I love that sound. So that’s kind of where the group started. It is an outlet for me to compose.

My goal with Le Percheron is to continue to play with those guys. I don’t believe in overnight success. We’ve been a band for five years now, and I think we’re just getting comfortable. My goal is to keep developing the group. Hopefully, those guys will all stay living here. I know Cory’s having a kid, and Noah’s not planning on going anywhere. Hopefully, Levi will stick around because we need him. How many vibes players are in town? Two? We’re a small town in that way.

I love that sound. I love that those guys are so willing to go with me down this road. I’m not trying to push it so we need to play all the time, either. I like to give things a lot of breathing room, so that when we do play we have something to play about.

Finally, in these times of pandemic, how would you like to see the jazz community respond?

Even before the pandemic, we were in a lot of trouble as a community. Like I said, we were losing clubs, more and more people were pretending to be able to do this. All of a sudden there were a lot of people flexing and I was like, “What are you talking about? You haven’t paid your dues. What are you doing here? Are you kidding me?”

And people started to devalue themselves quite a bit. It became very competitive. I saw a really sad cartoon – I think it’s kind of funny – that shows a jazz club pre-coronavirus: a bunch of guys playing on a stage to an empty club. Then post-coronavirus it was the same thing: a bunch of guys playing on a stage to an empty club. And I’ve noticed over the last four or five years, the scene kept going downhill in my opinion. Fewer and fewer places to play. More people getting competitive about it. The older guys going, “What about me?” and the younger guys going, “What about me?” The people in the middle going, “What about me?” Everybody’s got their arms up going, “What do we do?”

I think post-coronavirus, we could definitely – and this is on my shoulders too – use our own small club that was open Wednesday through Saturday, Clown Lounge style. Seventy-five people could smack in there and experience the music like we used to do it.

When we lost the Artists’ Quarter, and the Dakota moved from Saint Paul and stopped becoming a jazz club, I knew that we were in trouble. We lost the Times. We lost the Clown Lounge. We lost a whole bunch of places. All of a sudden we became a home entertainment society. If you watch HBO, their motto now is “Stay Home” – this was before coronavirus – “just stay home and watch our service all night.” I think fewer and fewer people are going to see shows. Fewer and fewer people are buying physical music. Fewer and fewer people are making music a part of their life.

I’m amazed at the younger generation, how they’ll get into a band for about six weeks and then they’ll abandon it. In my time, if you loved something, man, you supported that thing probably for your whole life. I haven’t stopped loving Iron Maiden. I haven’t stopped loving AC/DC. I haven’t stopped loving De La Soul. I haven’t stopped loving Wu-tang Clan. I haven’t stopped loving going to the symphony. But a lot of people have. And we lost a lot of people, a lot of people died who were very influential, who were very much a part of keeping the stream alive. And they haven’t been replaced, that’s what I’ve noticed now. When a big artist dies, like when Tom Petty died, there’s no Tom Petty to bring up the slack. There’s no band that’s like “we’re the next AC/DC.” There’s no band that’s like, “We’re the next Public Enemy.” I don’t know why. I just think you would have such a great audience because you’re appealing to an older crowd at this point. I think music has become something that people think should be free, no matter what genre it is, and it should be disposable. “I should be able to listen to it and throw it away,” ya know? “It’s in my life, it’s out of my life, because that’s easier.”

You wanna have a jazz club where people unplug from their phone for four hours and try to have a good time. We just don’t have that right now, and I don’t know how to rectify that. I’ve talked to a lot of musicians about it. I’m down for booking a club, I just don’t want to run it as a manager. That’s the thing when people are like “well, why don’t you have your own music school?” Here again, its a huge investment of time and money. I didn’t get into music to be a full time teacher. I was pulled into teaching because I was always a good performer.

I don’t wanna open a club to be a club owner. I think Kenny Horst at the Artists’ Quarter went through this a lot: “Am I a drummer? Am I a booker? Am I a father? Am I a family man?” And I love Kenny to death. He was so good to us when we were young and when we were old. He’s a true musician. And I didn’t always dig his playing when I was younger. But as I got older, I was like,”Oh, this is just you. I get it now.” (laughs) He did so much for this town. And Lowell Pickett back in the day really did a lot for us, but unfortunately I feel that the Dakota asked the local scene to build them up, and then left us behind after that was done. All of a sudden it’s funky blues night at the Dakota because Richard Erickson – who owns all the Holiday gas stations – is the other owner and we don’t wanna piss him off because he doesn’t like jazz. I’ve met Richard and I go, “Hey didn’t you just buy the Dakota jazz club? That’s great.” And he goes, “Yeah, I hate jazz.” I was like, “Oh, ok, seems weird, you know?” (laughs).

I don’t know what the solution is, but I’ve talked to older musicians like Phil Hey and the jobbing musicians I used to job with, and this happened in the 70s when rock ‘n’ roll kind of killed jazz. But there were still places to play five to seven nights a week if you wanted to. Things would come back in the 80s with the corporate money behind it, and big pre-Internet money behind it. So when I was growing up, jazz musicians were pretty flush. They all had best threads on, and cars and families and vacation homes. Guys were making a lot of money playing music. And I was like, “I’m in, whether I do it locally, or whether I do it nationally, or internationally, that’s what I wanna do.”

Now it’s a little more difficult for me to tell a young person that because I want them to be totally realistic to what’s going in the world, and unfortunately we’re losing the battle, but who knows? Who knows what’ll happen.

I’m hopeful. The funny thing about the Twin Cities is that we take things for granted until they’re not there. And then we kind of just shrug our shoulders and keep going. Maybe we need to fix that mentality before we fix the other stuff.